The Complementary Nature of Japanese Religion

This is a rather weak paper I wrote for my Japanese religion class. I though maybe some of you might want to read it but it's long with a pathetic ending so be prepared. Also, if you'd like to see pictues of the Sanja Matsuri mentioned at the end then see the album in my photobucket (I think its titles sanja matsuri). Also...the footnotes did something wierd so deal with them as best as you can.

There exist in Japan two major religious traditions, Shinto and Buddhism, which have grown over time to sit side by side in the everyday lives of the Japanese. Although both of these religions have their own long histories they have been molded together in contemporary Japan, as well as separated and given their own distinct functions in Japanese life. I will illustrate these two ideas, which probably seem contradictory, with two specific experiences of my own; my “religious” activities with my host family and the visits I have made to Asakusa Jinja especially in reference to the Sanja Matsuri.

Shinto is the folk religion of Japan and the beliefs are associated with different kami, or gods of nature. Initially the religion revolved around communities and villages and the kami were typically associated with their own needs (protection from natural harm, agricultural profit, etc). Unlike Shinto, Buddhism is an imported religion from China via Korea. While Shinto remained a major religion for the common folk, Buddhism was a religion that moved outward, having been adopted by the aristocracy first. During the Nara period and into late Meiji, it was not uncommon for Buddhist temples and Shinto shrine to be built next to or within one another[1] and from the Kamakura period on, Shinto and Buddhism’s relationship, with Shinto playing a primarily subordinate role, was explored and developed. During the Meiji restoration, in an effort to create some Nationalistic pride by drawing on the idea of Ujigami in Shinto tradition (the idea of community being strong and secure), Shinto and Buddhism were separated and the government created State Shinto. After the defeat in World War II, however, freedom of religion as well as separation of religion and state was established thus abolishing State Shinto.

This brief overview of the history suggests an already deep intertwining of Shinto and Buddhist ideas and thus gives us the framework for the complicated religious positions the Japanese are in today (although it probably doesn’t seem so complicated to them).

I will now present my first illustrator of Shinto and Buddhist complimentary nature: The host family I have been living with for 9 months now. When I first arrived in Japan I was surprised when my host mother asked me if I was religious. I replied that although I was a Christian I was not really religious, as in going to church every Sunday religious. I then asked if she was and she replied similarly, that she (and her family) was Buddhist though they weren’t religious. At the time, I didn’t really think much of this answer and assumed it applied the same way my “not really religious” sentiment applied. Since that conversation I have participated in several Shinto traditions with my host mother, from higan to hatsumode, as well as visited a few Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, at which she has always made a prayer and offering (and if her children are with her, gotten them to as well). When we went together to hatsumode, we went to a Buddhist temple. Hatsumode is of course a Shinto tradition, and although she did not pray at the temple she did buy a fortune for the New Year. We also stayed to hear the first ringing of the bell. When she told me the bell rings 108 times I asked her why. She did not know the response but I have since learned that the number could possibly signify the 108 temptations the Buddhist tradition warns of.

This experience illustrates several ideas about the contemporary approach to religion. She is not unlike the majority of Japanese who simply move through one tradition to another without pause or hesitation. I am not even sure if she is aware that she moves through both Shinto and Buddhist rituals and activities at once and throughout the different aspects of her life. But still, according to statistics, she is at least somewhat closer to the idea of “not really religious” because her household has no kamidana or butsudan, Shinto and Buddhist alters which house household deities and honor family ancestors respectively. In many households in Japan both of these religious shelves are featured, whether or not the household members consider themselves religious or not.[2]

While we had gone to hatsumode, a primarily Shinto event, earlier that fall we had gone to Yokohama to visit the grave of my host father’s mother. At the time I did not know this was the Buddhist tradition of haka mairi, visiting graves to clean them and make offerings, and more specifically higan, which takes place in the spring and fall. I was even encouraged to light incense and stand before the grave as well. This not only further illustrates the Japanese ability to move from one religion’s activity to another without feeling any sense of contradiction but also illustrates the idea that these activities are not considered so religious at all, and even if they are, that actual subscription or association to the religion is not necessary.

I was encouraged to participate in both events, and have been encouraged to attend and participate in many other events by my host mother (including Seijinshiki, coming of age, which I attended in full kimono) despite the fact that I am not Shinto or a Buddhist, nor did I have any knowledge of the religious association of the events. Reader writes, “In fact many Japanese people I have talked to about hatsumode hardly consider it a religious festival at all, and are reluctant to view their participation in religious terms.” He goes on to explain the social obligation of both events.[3] Hatsumode, as are many festivals, is a cultural event where communities come together and nearly everyone is there. There is a certain amount of obligation to go to such events built up in Japanese society and hatsumode is perhaps the religious festival most attended by old and young alike,[4] suggesting it has a certain part of popular appeal as well (though my host family must once more be an exception as my host mother and I were the only ones to attend this year). Haka Mairi is also deeply entrenched in social obligation, though this is in regard’s to one’s ancestors rather than one’s community. Family obligation is a major part of Japanese lifestyle and history and was a major influencer of the development of Buddhism, yet despite this, higan is not nearly as popular as hatsumode.[5]

Even if these activities were considered religious and not simply social traditions, my being encouraged to participate during higan illustrates another idea imbedded in Japanese religion. Swyngedouw presents the ability of compartmentalization that the Japanese have with the use of two terms wa and bun. What we have seen is that Japanese can move from one religious association to another with a certain sense of harmony and without regard to any contradiction of ideas; this is wa. This ability to be at peace with the different associations comes from bun, the assignment of each religion and activity to its proper place. [6] Today, the major religions are each associated with their own aspect of life; for Shinto for birth rites, coming of age, etc, for Buddhism for funerals and honoring ancestors, etc, and, as of late, Christianity for marriage. It also implies the idea that these boundaries are not to be overstepped, and the idea that once one event is over you may simply return to normal life.

This leads to another idea which Reader describes when he talks about certain situations in life demanding certain religiously associated activities in the Japanese mind.[7] If someone dies then someone in the family must go to the temple to learn about the appropriate actions (indeed, although though many Japanese say they are Buddhist they often never find out what sect they are a part of until someone dies[8]), if there are entrance exams then students go to a temple or shrine to pray, and so on. When they do so they are completely involved in whatever frame of mind is necessary and there is no qualm or hesitation about facing a changing doctrine or requesting benefits from different religious organizations.[9] The phrase for this is kurushii toki no kamidanomi, turning to the gods in times of trouble, and for the Japanese this can mean any god regardless of religious activeness or association.[10]

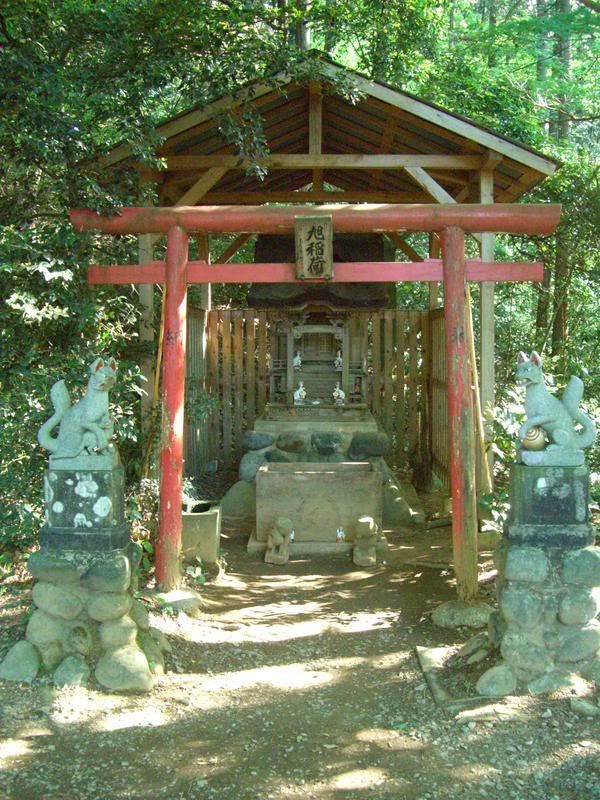

It is not just the Japanese lifestyle that is affected by these developments of Japanese religion. I will now briefly discuss Asakusa Shrine in relation to the complementary nature of Shinto and Buddhism. Discussion of Asakusa actually requires the introduction of Sensoji Temple as well. As I mentioned earlier, from the Nara period on Shrines and Temples were built with one another. Sensoji and Asakusa were once such a complex though they were separated after the Meiji restoration. The Buddhist temple and Shinto shrine are still, of course, right next to each other and so much associated with each other that the largest matsuri (festival) to take place there, the Sanja Matsuri, is associated with the temple and the shrine-while researching I could not find anything that said it was specifically dedicated to one or the other location, instead they both seem to claim the matsuri as their own. Indeed, although I had been there many times it was not until my last visit that I realized the temple and shrine were separate locations, for they are so close together, and their architecture so similar, that they could still be the same complex (which is not surprising since they once were).

Architecture alone is enough to illustrate the influence that Buddhism has had on the Asakusa shrine. Most shrines are designated by Tori, gates, which lead to the shrine but Asakusa is preceded only by the huge and domineering Kaminarimon, a Buddhist gate primarily associated with the temple. Still, the most noticeable Buddhist structure is the Pagoda, which in Buddhist tradition houses relics of Buddha and in this temple’s case, those of the Kannon Bosatsu. The architecture itself is Chinese appearance including the painting which is vivid red and includes elaborate paintings on the inside ceilings.[11] While all of this shows the Buddhist influence on the shrine, matsuri are traditionally Shinto events. The Sanja Matsuri includes the procession of hundreds of mikoshi, elaborately made portable shrines to carry diety, from Asakusa to Sensoji. Despite the fact that this festival, as are all matsuri, is associated with kami, it is tied to Sensoji temple. Of course, this festival is not just for religious means, it is also conducted for the sake of the community and the sake of the festival itself.[12]

The relationship of Shinto and Buddhism is one of give and take in the lives of the Japanese. This is not to say that they are the only two religions, or that Japanese cannot have a singular religious belief. It is simply that the majority of Japanese society exhibits this sense of compartmentalization when it comes to religion, and ability to harmonize, that it is no wonder the two are so deeply intertwined.

[1] “Shinto Shrine”, http://www.wikipedia.com/

[2] Referring to the NHK survey information Swyngedouw relays in his article: “In 60% of the homes surveyed there was a kamidana, or Shinto god shelf, and in 61% a butsudan, or Buddhist altar. About 45% had both and only 24% had neither.”

Jan Swyngedouw, “Religion in Contemporary Japanese Society,” Religion and Society in Modern Japan, pg 54

[3] Reader writes about Hatsumedo and O-ban in relation to social obligation as well as the fact that regardless of this they are still attending religious rites and locations for said events.

Ian Reader, Religion in Contemporary Japan, (London, MacMillan, 1991), pg 11

[4] Referring to the high percent of people both young and old who attend hatsumedo according to the NHK survey: “hatsumedo scores 81%, with little difference between the younger and older generations…”

Swyngedouw, “Religion in Contemporary Japanese Society,” pg 55

[5] The stats here say that while many older people still participate in Higan, the younger generation is not

Swyngedouw, “Religion in Contemporary Japanese Society,” pg 55

[6] Swyngedouw, “Religion in Contemporary Japanese Society,” pg 62-63

[7] Reader states “There is a deep relationship between situations, actions, and religiosity in Japan. Situations demand actions that express a latent religiosity…” and then goes on to talk about a reaction to death and the steps taken through buddhism

Reader, Religion in Contemporary Japan, pg 15

[8] Referring to reader’s anecdote about a friend who stated this when asked what sect he was part of, plus the other many times I have heard this anecdote

Reader, Religion in Contemporary Japan, pg 3

[9] Swyngedouw is introducing his thoughts on the structure of Japanese religiosity and states “even when the Japanese engage in religious acts, there seems to be no coherency in their behavior.”

Swyngedouw, “Religion in Contemporary Japanese Society,” pg 60

[10] Reader, Religion in Contemporary Japan, pg 20

[11] “Architecture: A Harmonious coexistence of tradition and innovation,” http://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JapanAccess/kenchiku.htm

[12] “Asakusa Shrine,” http://www.asakusajinja.jp/english.html (2007)